a sermon for the Resurrection of Our Lord, Easter Sunday

John 20:1-18 and Isaiah 25:6-9

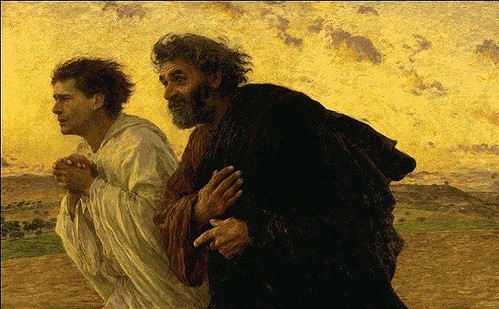

Early on the first day of the week, while it was still dark, Mary Magdalene arrives at the tomb and sees the stone has been removed. Her first response? She runs. She runs! In the dark, to two of Jesus’ disciples, to tell them what she’s found and what is their first response? They run. In fact, it’s a race—a race to the tomb to see who can get their first. Lots of running, especially first thing on Easter morning. None of the other gospel writers have quite so much running, but John makes sure we know. At this point this seems less like a cemetery scene and more like…first grade recess.

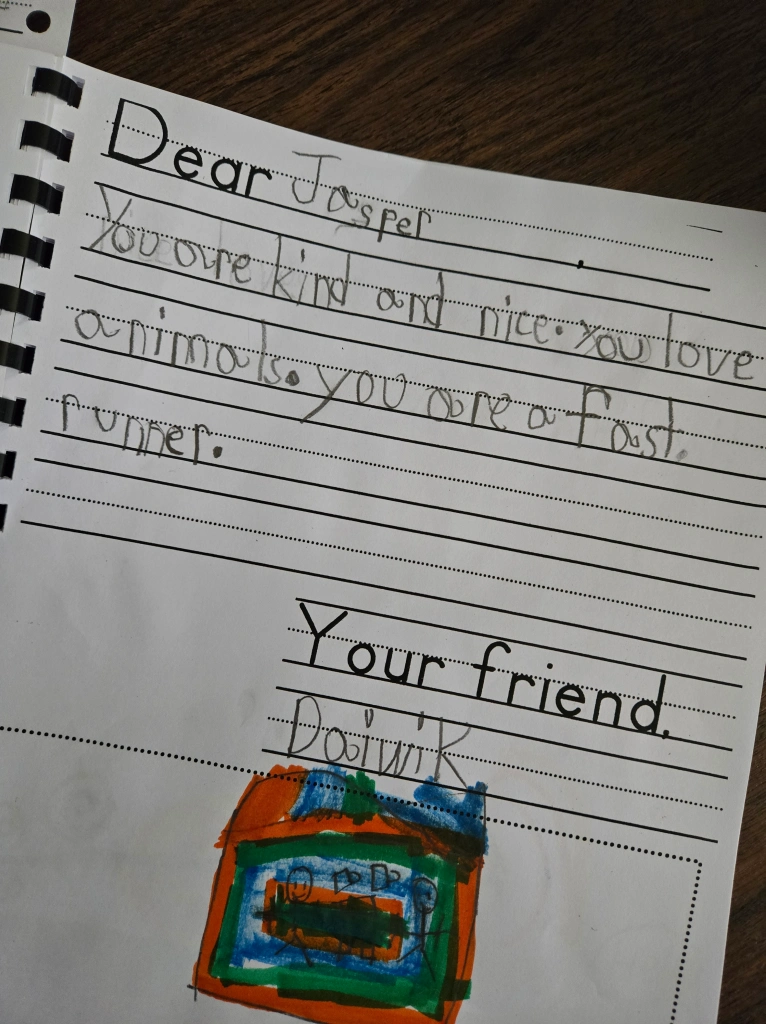

First grade recess, in case you don’t know, is all about running and racing and who is fast and who gets beat. And maybe I’m just reading too much into this resurrection scene, but you have to understand our own first grader came home this week—the same week I was preparing for this sermon—with a booklet his class had made him. Each kid was asked to write a few short sentences about him (he was the “Star of the Week”) to praise him and make him feel proud about himself. Flipping through the pages, we sensed a theme:

“Dear Jasper, you are kind and nice. You are a fast runner.”

“Dear Jasper, you love animals and you are a fast runner.”

“Dear Jasper, you are like a cheetah because you are so fast!”

But that’s the playground at school. This is a graveyard, and there are allegations of body-snatching. What’s going on? Are the disciples and Mary Magdalene just excited? Could someone with evil intentions be onto them, ready to ambush and arrest them too? Bible scholars have long speculated about what might be going on here at the scene of the resurrection. Some have suggested that the unnamed beloved disciple was younger than Peter. Fresher, stronger legs helped him run faster than the arthritic Peter.

Others have interpreted more serious differences into their running speeds. For example, if Peter is traditionally seen to represent Christianity’s Jewish roots, and the beloved disciple, who is most likely John, to represent Gentiles, then it is important that Peter be the first one into the tomb, since Gentile Christians come to faith only after the Jewish Christians do.

Still others read this footrace as symbolic of the competitive nature between Christianity’s two earliest strands, the ones who formed around Peter’s leadership and those who were more closely associated with John’s. Was their desire to outrun one another a sign of early dissention and rivalry?

Another theory is that these two guys were racing for publishing rights to the story so they could sell it for $69.99, plus shipping! I am not a fan of that theory.

Most of these assumptions are fun to entertain but they will never be resolved. Maybe we should re-direct the question: did you run here this morning—if not literally, with your feet, then with your mind? Why did you put on the Easter finery and force the little ones into theirs? Do you harbor an inner desire that this weary, war-torn world be changed, shaken up? Are you hopeful for a new beginning out of the ashes of your past?

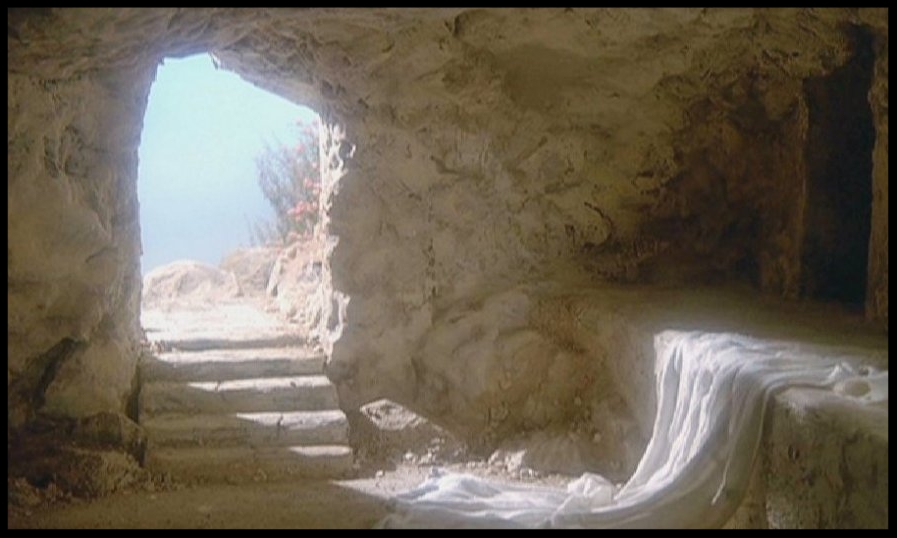

In some ways, however, being fixated on all the running only detracts from what is really important here: Jesus’s body is no longer in the tomb and there aren’t too many good reasons for that which immediately come to mind. It isn’t until they each take turns going into the tomb itself that it begins to dawn on them what has actually happened. The stone is rolled away and the tomb is empty because Jesus is risen.

The graveclothes are a clue: stolen body would have not left costly linens behind, for those were not only valuable to tombraiders in the marketplace, but useful in carrying and relocating or maybe even hiding a corpse. But there they are, some of them even neatly rolled up, which makes me a little resentful that the first thing Jesus does in his risen life is make his bed and fold the laundry. Interestingly, the writer of the gospel tells us that the beloved disciple sees and believes after he enters the tomb. But then we’re told that neither of them fully understand the meaning of the Scripture about the resurrection.

I don’t know about you, but I find this to be a very realistic detail about their response to this amazing event. All too often belief in something—or trust in God, if we want to think of it that way—does come before truly understanding it all. We see this in several of the people Jesus meets throughout his life—people like Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea, those who actually show up at the end and prepare the body for burial—people who are drawn to believe and to expand their faith but who don’t immediately have the comprehension or courage of convictions to back it up.

I bet it is where many of us are today about many things regarding faith. We are amazed, we are curious, and we even might stake our life on something about God, but we don’t fully understand it. Like the first disciples, we are drawn to hear the news and maybe even to trust it—

to trust that God really has overcome the powers of darkness and evil; to trust that in Jesus God has claimed this world for good; to trust that on the cross Jesus was lifted up that all of humankind would be drawn to God, not just select ones.

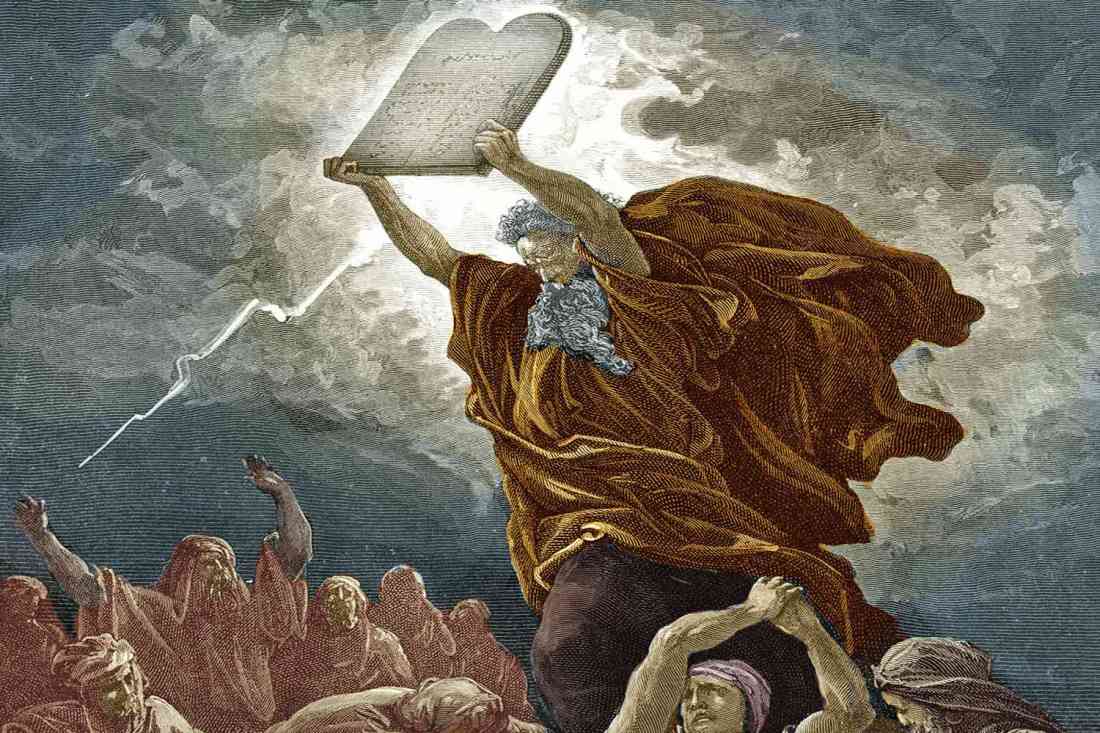

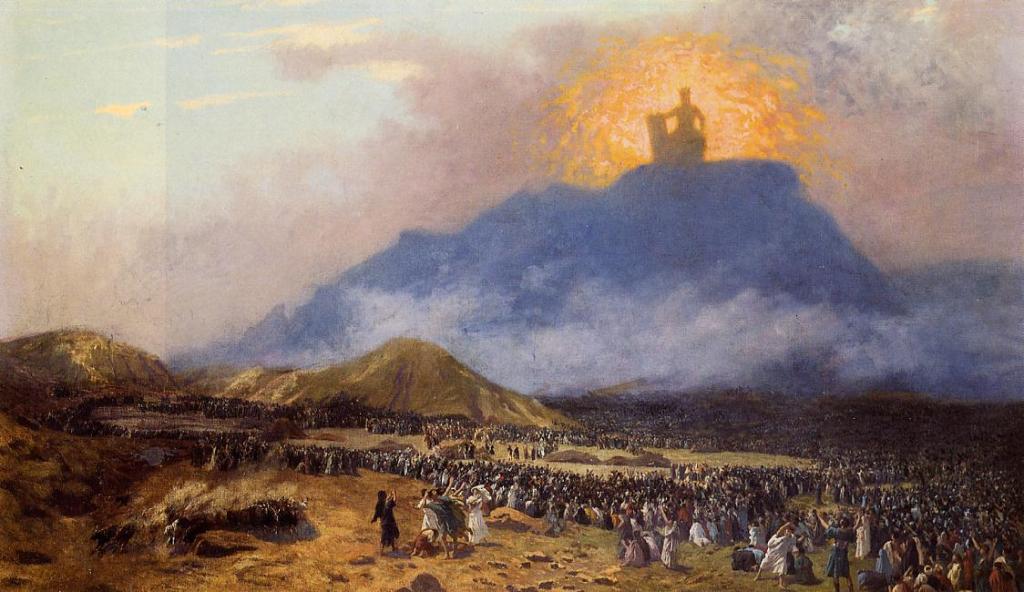

As the prophet Isaiah declared centuries before, we are drawn to trust that vision of a life where all God’s people are gathered to God’s holy presence where gifts of God’s goodness are not held back and we sing and we rejoice that death has been swallowed up forever. The shroud that that is cast over all peoples—the graveclothes that are spread out in the tomb—will not just be folded and set aside, but destroyed. And God will wipe away every year from all faces. This is the vision some of us trust, others of us run to, still others hold back in grief and suspicion.

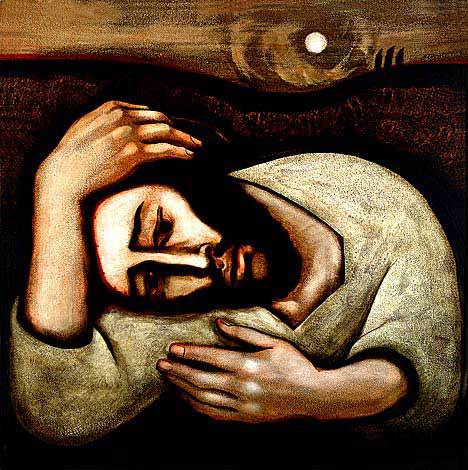

Which is why we must be thankful for the one who doesn’t get caught up in a footrace that first morning, Mary Magdalene. She does have tears on her face that still need to be wiped away. Mary Magdalene lingers—lingers in her grief, in her dismay, in her confusion. She’s the investigator here, the detective, the one who still wants to know what has actually happened to her Lord’s body. It’s not faith she lacks, or understanding, or grasp of the Scriptures, but more the details. Maybe, deep down, she still seeking word from her Savior, himself, and the only way that will happen is to open those emotions up.

When she finally sees Jesus, she supposes him to be the gardener, the groundskeeper, and in a way, that’s exactly what he is. Like one who tends the earth, he is skilled at bringing forth new life, even in us. He can make an ordinary scene beautiful, an area of mud and stone teem with life. In this case, it’s the whole cosmos.

Last week at one of our men’s gatherings someone happened to mention the Easter of four years ago, right at the outset of the pandemic, when we had to pre-record everything because we couldn’t gather in person. This gentlemen said what stuck out to him the portion of that worship video where we asked people to record themselves responding to the Easter proclamation of “Christ is Risen! Alleluia!” with “He is risen, indeed! Alleluia!” What struck him was that people recorded those messages in their gardens, some people standing against a backdrop of vibrant azaleas or a dogwood tree.

I had clearly blacked out that component of pandemic worship (I’ve blocked out a lot of the pandemic) so I returned this week to our YouTube channel and scrolling back through all hundreds of videos, watching Pastor Joseph’s hair start long and then get steadily shorter back to April 12, 2020. And as I watched that segment of that worship video again, the part with people sharing their joy from their own yards and gardens, many in selfie mode, I was reminded in an emotional moment just how those clips spoke resurrection to me, lost as I was in my COVID darkness. It was almost too much for me to watch. We were so distant then, afraid, isolated. I had figured each of you then just to be gardeners on the screen, but in a real way you were the very presence of the risen Lord. Your smiles and your words called through the screen in a way that resonated deep inside of me. And I don’t think I was the only one who felt that way.

What Mary’s encounter by the tomb teaches us is that Jesus always seeks to bring clarity to confusion, hope to despair, new life to death. He is patient, unperturbed by our lack of understanding. We have a Lord who comforts by calling us by name, which is to say in ways that make us feel known and understood and claimed. God has raised Jesus, today and every day. The graveclothes are folded and bed made. A new, unending day of possibilities lies before us all.

So, whether you’ve run here today, for whatever reason, eager to believe, or whether are lingering at a point in your life, looking for more facts, more evidence, more clarity…may you trust that the God who raised Jesus from the dead is patient and caring, persistent and willing to wait for faith to come. But if you should believe and trust this message of Jesus’ victory over death then run along now. The world is waiting to hear what you have to say. Run along now. In fact…I know someone who’d be happy to race you.

Thanks be to God!

The Reverend Phillip W. Martin, Jr.