a sermon for the seventh Sunday after Pentecost [Proper 12C/Lectionary 17C]

Luke 11:1-13 and Genesis 18:20-32

I bet we can think of the person who taught us to drive. We can probably think of the person who taught us how to bake cookies or make a meal using the stove. Each of us can probably think of the person who taught us how to play a musical instrument or throw a ball. There are a few high school seniors here who will be heading off to college in a few weeks. I bet if they haven’t learned it already, someone will be teaching them soon how to use a washing machine and dryer.

Last night one of our members who is at the beach with her extended family this week posted a photo on Facebook of a bunch of adults huddled around a coffee table with some elementary school age children in a dimly lit room. On the table were some playing cards and some chips with the caption, “Teaching the older girls how to play blackjack and poker at the beach…they are big stuff.” My guess is those girls are tired from the sun and the sand and the salt but they are always going to remember when their moms and dads let them stay up a little late and taught them how to play grown-up card games.

Can you think of the person who taught you how to pray? Perhaps you are still wondering how. We may not at first think of prayer as something that needs to be taught. My guess is that many people would think that prayer is so personal, so unique to each person’s own spirit and perspective, that the idea of teaching prayer sounds authoritarian or doctrinaire. Who are you to tell me how to pray?

And yet we know that Jesus’ taught his disciples to pray. In fact, it’s the only thing we know of that Jesus was specifically asked to teach. In both Matthew’s and Luke’s gospel we have stories of Jesus returning from a time of quiet prayer and the disciples wanting him to show them what he’s doing. I imagine they’re pretty intrigued. In those days, the disciples would have most likely associated prayer with something that happened in the Temple or in the local synagogue, something that the rabbis, priests, and other worship leaders did or knew how to do. The disciples see that their leader is constantly going off somewhere to pray on this own, that this praying somehow fuels him and gives power to his ministry, so they naturally ask him how to go about it.

We find that Jesus’ arm doesn’t need to be twisted one bit. He gathers them around the coffee table, sees their faces eagerly looking up to see what he’ll say. And instead of telling them about a certain position or posture they need to be in or telling them that they need to meditate he actually gives them words. He gives them a real, usable pattern to go by. It’s perhaps the purest example of grace. They ask and he gives. They knock and the door is opened. It’s a real, biblical example of faith formation.

This past Lent the staff discovered, almost to our surprise, that people still respond well to the concept of prayer and teaching someone how to go about it. When the staff came up with the theme for Lent 2019, we decided to continue with the congregation’s focus on faith formation and present different forms of prayer. Some of you may remember that we incorporated an interactive aspect to the sermons. When we learned about prayers of thanksgiving, for example, we were invited to write on a cut out of a flower things for which we were thankful and then to come forward and place that flower on a large board that came to look like a field. When we were taught about prayers of lament, worshippers were given a piece of torn cloth that they wrote on and then came forward to tie on a wooden cross we had set up in the middle of the aisle. We did this for five different kinds of prayer, thanksgiving, lament, and then supplication (asking for something), adoration, and confession.

Now, I have to be honest and admit that even though I was part of the team that came up with this idea, I secretly worried that the topic and the interactive component would go over like a lead balloon. I couldn’t have been more wrong. People seemed to really respond to the opportunity to learn about the forms of prayer and physically participate in practicing it. The staff talked several times about how moving it was seeing people so eager to express themselves to God.

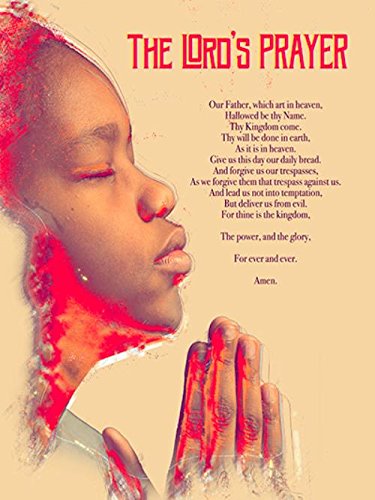

The prayer that Jesus teaches his disciples that day catches on immediately. They must have responded well to it because we have evidence from the earliest times of Christianity that followers of Christ were praying this prayer and following this pattern. It has come to be known as the Lord’s Prayer, and here at Epiphany you may notice we use two different versions of it. There are actually many different translations of it, as you can tell from this morning’s Scripture. With it Jesus says that these are the best types of things you can pray for: that God’s holiness and power be made known through us. That our truest needs be given just for today. Tomorrow can worry about tomorrow. And so forth.

The Lord’s Prayer has become so ingrained in our usage that some of the truly groundbreaking parts of this prayer may be lost on us. For one, Jesus tells his disciples to address God in the same way that he himself does, in the most familiar and endearing terms possible. In fact, the word “Father” might best be translated as “Daddy,” and that word doesn’t imply anything about God’s gender or masculinity but rather the parental relationship Jesus has with God. All of the pronouns used by Jesus are the informal means of address. Many languages have what is called a formal “you”—used when talking to someone like a professor or an adult you want to show respect to—and an informal “you,” which one would use when speaking to a close friend. Nothing about the language Jesus gives to his disciples suggests we need to be formal when addressing God. He says we are to just talk in the way we’d talk to our friends.

I remember when I was in youth group we were gathered around one evening for our meeting and our leader asked for a volunteer. I know this may surprise some of you, but I was the kind of kid who’d throw my hand up before I knew what I was being asked to volunteer for. I raised my hand eagerly and the leader called on me and said, “OK, Phillip, pray for us.” I was mortified because I’d never had to pray in front of anyone before, much less all of my peers. I felt like Ben Stiller’s character in that scene from Meet the Parents when he has to say the table prayer in front of his fiancee’s family. I ended up bowing my head, pausing nervously for a really long time, and then bursting out with “Um…God?” like it was a question. And everyone in the room burst into snickering. I felt so stupid. Who starts a prayer with “Um?” Well, the tone of the Lord’s Prayer suggests that God loves to hear that kind of honest plea even if there is merit in being more direct and succinct with our words. God doesn’t grade us on how we begin, how we open our hearts, what language we use, how repetitive we are.

That’s why it’s helpful to use this newer version of the Lord’s Prayer that incorporates more modern language. Many of us are so familiar and attached to the version that came out in 1611 with the King James Bible, and that’s OK, but the new version matches more closely that familiarity that Jesus teaches his disciples in the Bible. I don’t know anyone nowadays who talks to a friend with words like “thy” and “art.” Being open to and even memorizing two slightly different versions of Jesus’ prayer has only enriched my prayer life, and I guarantee it will yours, especially since many of the earliest Christians believed that Jesus intended this prayer to be more like a pattern than a rote saying.

Whatever language we use, however, Jesus then goes on to say that prayer involves action. It is like knocking on a door in the middle of the night so that you can be a good host for someone who’s dropped in. It is like receiving food from a parent’s hand so that you can eat. Jesus implies there is nothing really passive about prayer. It may be done in quiet from time to time, but it is active, and it moves us to action, just as it moved him to action to love and serve us. His last words upon the cross were prayers, as he gave up his life to show us his mercy and forgiveness.

Seeing this gets us to the real heart of prayer—that it is not so much about getting God to do things for us as it is about joining our lives with what God is doing in this world through Jesus. Christian prayer does not come from a place where we see ourselves as the center of our own lives. It is not about centering primarily on what’s happening to me and figuring how God might fit in or how God might be moving in my life. Jesus says we pray, “Your kingdom come.” When we pray as Jesus teaches us we are tapping it whatever mercy and compassion and love God is bringing about in creation. Our personal needs are surely important and understood by God, who gives what we need without our even asking, but prayer does something even mightier than make those requests known to God. Prayer cracks open our hearts and aligns us with God’s intentions, God’s plans.

That’s precisely what is happening in this interesting dialogue between Abraham and God in Genesis. The heart of God is compassionate and merciful and Abraham knows this. He doesn’t particularly like Sodom and Gomorrah, but his brother and his family are staying there The city-people have sinned against God by treating the visitors with extreme inhospitality. They needed a place to find refuge, and the people of Sodom and Gomorrah took violent advantage of them. Abraham stands before the Lord, however, and asks for mercy. He appeals to the way he knows God moves in the world, the way of God’s heart even though he knows God’s anger is kindled against them.

I have seen this kind of praying among this congregation so often—ways that push them further into the vision for God’s kingdom and God’s will. Just yesterday as I spoke with members of our HHOPE Pantry team. The HHOPE team is very diligent about their own time of prayer together each time after they serve, and over the past several months they have seen a decrease in the number of people using the pantry. Now, there could be any number of reasons for that, but their prayers have led them to reassess their ministry, their outreach. They are now considering a strategy to reach out to additional schools to heighten our profile, to reestablish contacts with their existing local relationships. God’s kingdom is coming when the poor are given hope and the hungry are filled with good things. And so instead of soldiering on the same way or making their ministry the center of what God is doing, they are aligning their goals with whatever the needs of the community are.

I realize that I’ve probably given you know clearer vision of what prayer is or how to go about it. In many ways, it like the disciples asked Jesus how to speak a language. And how do you really learn a language other than start speaking it? If you want to learn how to pray, if you are wondering how it all works, if you are struggling to see the point, may I humbly point out some people in our midst who are native speakers. Join up with them or another group like them. Knock on the door and you will find your heavenly Father, who is gracious, gives the Holy Spirit.

Thanks be to God!

The Reverend Phillip W. Martin, Jr.