a sermon for the Fourth Sunday of Easter, Year B

Acts 4:5-12 and John 10:11-18

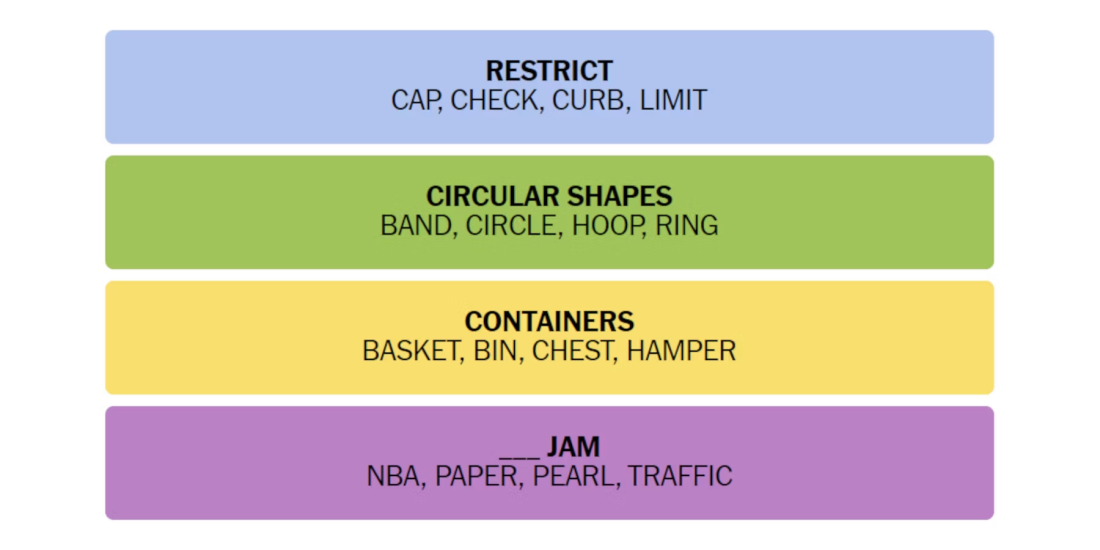

For those of you who are using our new online membership app, Realm, you may be aware that two-factor authentication was just launched a few weeks ago. Two-factor authentication is an on-line security feature that many Realm users had been anticipating and hoping for, as two-factor authentication asks for users to use two distinct forms of identification before allowing access to personal information. For example, if you log in to the app using your phone, then it might send an email with a special login code to make sure you are really who you say you are.

Even if you haven’t made the shift to using our Realm app, my guess is that you have encountered it with banking or social media information. I’m pretty sure even the app I use for birding uses two-factor authentication when I try a new device because, you know, my bird life list is top-secret, sensitive information. OK, not really.

Like it or not, we live in an age of passwords and passcodes, and login IDs, and verification schemes. To get into anything, we have to create a very clever combination of numbers and letters and symbols and Zodiac signs and emojis and woe to the person who forgets what they’ve come up with. Then the whole process starts over with a new email and a new login code for that. I just long for one name!

All of this is to say that this is what it sounds like Jesus is like in this story from Acts when Peter rises before the tribunal of religious authorities. It sounds like Jesus is some sort of passcode or two-factor authentication for salvation. “There is salvation in no one else,” Peter says, filled with the Holy Spirit,“for there is no name under heaven given among mortals by which we must be saved.” It sounds as if God has set up heaven like some sort of tightly locked up bank account and the only way you or I or anyone else can gain access to it is to type in the right word, which is Jesus.

Chances are you have probably heard Peter’s sentence used that way at some point. I know I have. Oftentimes this verse is used as some kind of mission or evangelism strategy. For example, people are told you don’t profess the name of Jesus or somehow figure out that code that God has set up then you are going to be out of luck when you die. And while I understand the comfort, the security, that may give some people, is that all Jesus is good for, as a type of passcode? In this rigid interpretation of Peter’s confession Jesus is no longer a person, someone you might have a relationship with, someone whose voice you might respond to. Jesus just becomes a device, a key to deliver something else that we might want, not to mention something cruel and divisive that condemns outsiders or people who don’t know the code to a dismal future. And clearly, if we look at what’s going on with Peter, he never means Jesus to be those things.

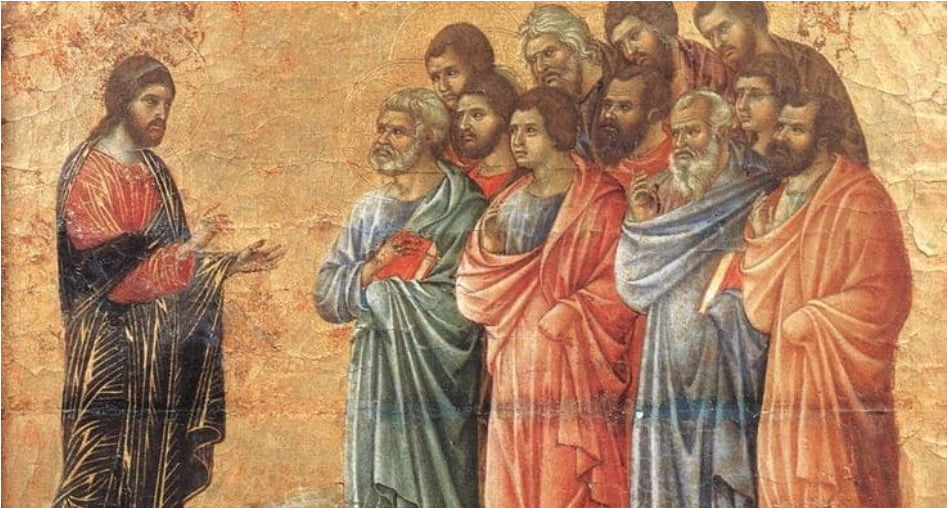

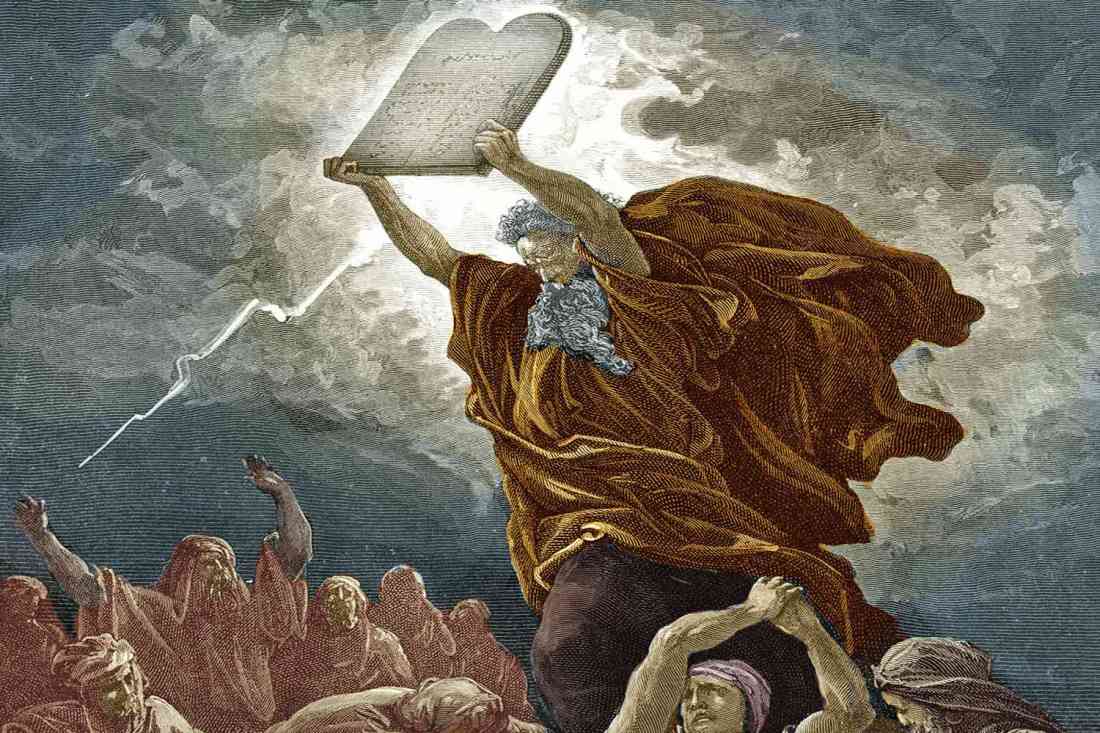

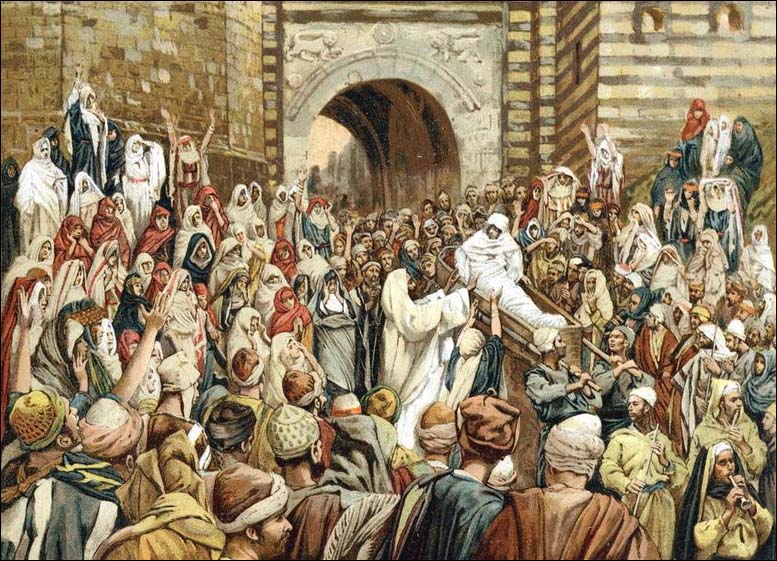

As some may remember from last week’s readings, Peter and John have just healed a man who was lame from birth. The man who is healed becomes a sign of God’s power that Jesus is the one God anointed to overcome the sin and evil in the world. The healing gets a lot of attention from the crowd, and now Peter and John are on trial before the religious authorities who fear the disruption that Jesus’ followers may bring and who want to stamp out any reference to Jesus’ name and story. In Peter’s testimony to them, the point of Jesus is not to just recite or claim his name so that you or I or anyone else can go to heaven when we die, but that we may run to Jesus now and receive forgiveness and mercy and unconditional love.

Peter wants his accusers and other listeners to understand that Jesus’ presence has power. Even if it is disregarded, God will just keep raising it up, over and over. Jesus can be trusted because Jesus’ love always works to undo and overturn the powers of sin and evil. Jesus liberates, Jesus frees people from oppression, Jesus heals the sick and forgives everyone.

Jesus does not condemn or ostracize anyone. Peter knows this and has seen the power of Jesus up close and is giving a defense of what has happened because he has been arrested and called before the authorities.

And that is crucial to understanding what is happening here. Peter is on trial. It is very likely that his life is on the line. He is not on the attack, so to speak, preaching a sermon trying to win people over, making sure they have their spiritual houses in order. He is making a statement to the authorities about what Jesus can really do. God has sent Jesus to rescue God’s people through his love and that is something Peter is willing to stand on even as they threaten to persecute him.

When have you come to trust Jesus? In what times have you realized that Jesus’ authority on love and life is something that can always be relied upon? When has your back been against the wall, so to speak, and you’ve realized that the words of Jesus, the way of Jesus, the love of Jesus is what threw you a lifeline? Have you experienced how the kindness and humility of Jesus has transformed a situation of anger and tension? Have you watched as a dead end in your life has somehow, unexpectedly and unpredictably given way to a new beginning? If you haven’t yet, Peter wants you to keep your eyes and your hearts open. He knows that these are the tried and true ways that the risen Jesus works to save the world. There is one name we can trust that brings this new life, and it is Jesus.

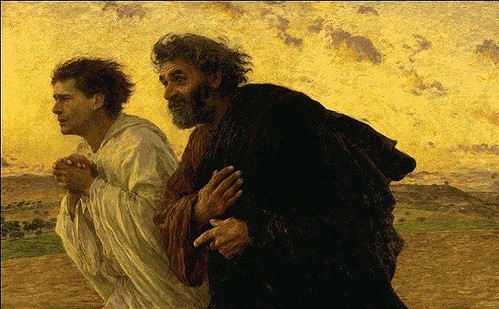

But there’s an important tension we can’t ignore. For even as we hear Peter claim that there is no name under heaven by which mortals can be saved, we also hear Jesus himself say that there are other sheep that do not belong to this fold and he will bring them also. People have long wondered what other sheep Jesus may be talking about here. Perhaps they are other congregations or groups of followers that his disciples may not have known about? Could Jesus be talking about the Samaritans, that ethnic group in Jesus’ time who were not considered part of the Jewish family? Is he meaning people of completely different faiths and religious communities, faiths and communities that may even coexist with us today?

It’s hard to say, but no matter how we may interpret it, it must mean there is a foundational graciousness to life with Jesus that we must be careful never to limit or confine. Living as Christ’s flock means always being attentive to the fact that others we perceive to be outside our community may, in fact, be the ones whom Jesus is leading, hearing Jesus’ voice in tones we don’t recognize yet. He is working towards greater unity in ways that we might not perceive. We can be sure of his love, but we also keep in mind that the abundant life that Jesus brings is always going to be bigger than any words or doctrines that you or I might find lifegiving at any given moment. As the Reverend Ben Cremer says, “our Christianity should sound like, ‘the world is full of neighbors to be understood and loved,’ not ‘the world is full of enemies to be feared and conquered.’”

For a few days this past week I travelled to Lutheran Theological Southern Seminary in Columbia, South Carolina, to take part in the last Alumni Days celebration before the seminary moves its campus to Hickory, NC, and the campus of Lenoir-Rhyne University. It’s the reality of most church life nowadays—declining numbers in seminary and in congregations have left enrollments so low that it is difficult, if not impossible, to sustain infrastructure from previous years…infrastructure like a separate seminary. This year’s incoming class has just two Lutheran students. Southern Seminary, as it is called, is the place where no fewer than seven of Epiphany’s current and former staff members and interns have received formation for church service. It is a special, holy place for many of us, and the time there this week was bittersweet.

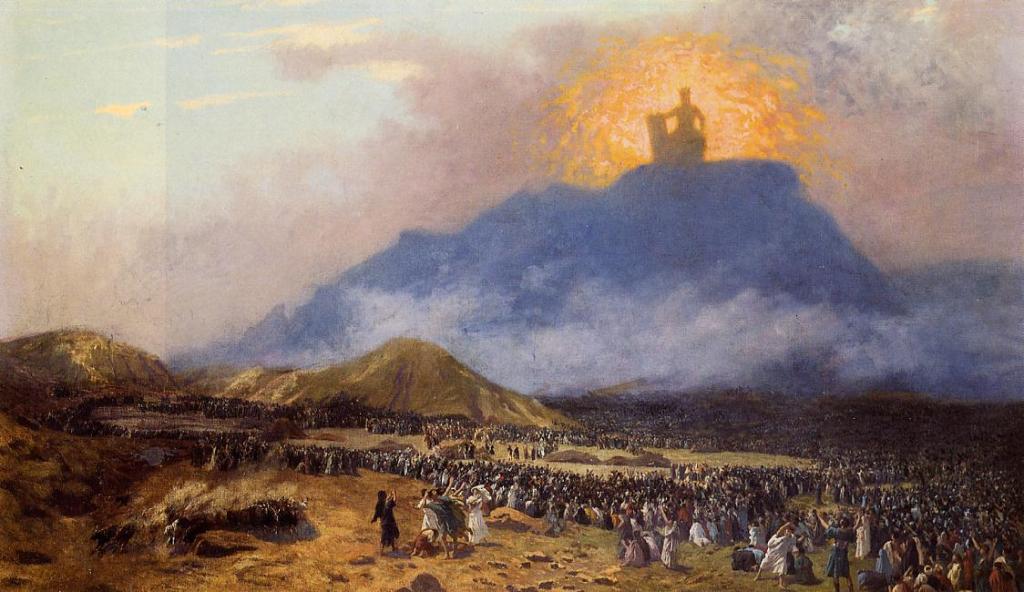

One of the things the seminary did for this week’s celebration was to pull out and put on display most of the past composite photo arrangements of the past year’s graduating classes. As we sipped our drinks we could walk through hundreds, if not thousands, of faces of people who had been shaped by the call to serve and sent out into the world. It was like a treasure hunt—going back through the years I found Joseph’s photo in 2007, then Christy Van O’Linda Huffman’s in 2005. I saw our visitation pastor Mark Cooper’s and then Tom Bosserman’s. I saw Joseph’s father in the class of 1972. It was really quite overwhelming, especially as I prepare to rest and refocus during a time of sabbatical, to see myself quite literally placed amid this great cloud, this huge flock of people, most of whom I do not know but who had nevertheless heard the voice of the Good Shepherd to serve as a leader in the church. It made me think of how I have a responsibility to encourage new people to hear that call to serve.

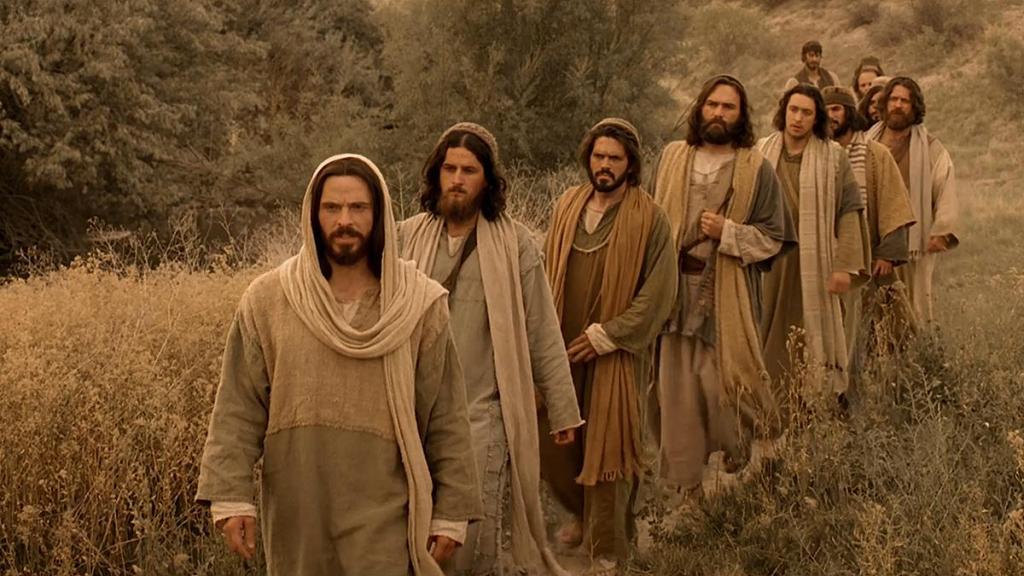

I tell this not to raise any anxiety about the state of things, but maybe because those composites got me thinking. They got me thinking about how the Good Shepherd might view all of us as he walks us through the world. We are all in different groups and categories at times, many of which we make up to separated ourselves in needless ways. Jesus walks through the world, gathering us all together—these from this ethnic group, those from that race, these over here from that gender, that class, that religion—into one big group together. We are patiently, lovingly assembled by a leader who lays his life down for the sheep. He keeps us safe from forces that snatch and scatter us.

And through the mission of the church our service becomes a demonstration of how Jesus is that Good Shepherd, that he ultimately is working to bring life to all, and that he does it always in ways that involve some kind of self-sacrifice. He goes through the valley of the shadow of death with us. And pours our cups to overflowing.

The world is full of people to understand and love. Rather than forcing people to make some kind of choice about Jesus and presenting him as a code for getting into heaven we should just urge people to hear his voice—all people. With the confidence of Peter we can testify to Jesus’ ability to heal and save, but with the humility of a sheep we can keep our ears trained on what he says, for he is constantly calling, constantly calling out to a composite crowd, one flock, one shepherd.

Thanks be to God!The Reverend Phillip W. Martin, Jr.